$12.7 million for homeless housing in Ojai, one year later

The latest on Ojai’s Cabin Village one year after the grant award announcement and a deep dive into projected revenue. Plus: the latest Ventura County homelessness numbers.

Greetings Readers!

Before we dive in, there’s something I want to say. I’m someone who has dedicated her career to government, politics, and democracy. Given that experience, I feel a responsibility to present this observation from Steven Levitsky, a Harvard political scientist and author of “How Democracies Die,” in the Los Angeles Times:

“We are currently witnessing the collapse of our democracy.”

I’m sad to say that I agree with him (as do hundreds of political scientists).

I also believe deeply that to engage with local government is to strengthen democracy. That’s the spirit in which I write.

$12.7 million for homeless housing in Ojai, one year later

Author’s note: this story was update at noon on Friday April 25th with an updated statement from Kimberlee Albers regarding grantees’ ability to put ERF money in a dedicated operational account and a statement from the “Friends of the Cabin Village.”

On April 18, 2024, the City of Ojai won 12.7 million dollars in state funding to build 20 units of permanent supportive housing in the City’s Kent Hall parking lot. The state grant — known as the Encampment Resolution Fund (ERF) — supports projects that provide a path to permanent housing for homeless individuals.

In the year since, Ojai’s grant project has morphed into 30 units of housing in the City’s public works yard. (For a fuller review, check out this timeline or my past reporting on the topic.)

Importantly, Ojai is not alone with this state cash infusion. Ventura, Oxnard, Camarillo, Thousand Oaks, and Fillmore have also received state ERF grants, totaling $41.1 million in funding to address homelessness in Ventura County. (I’m very excited to cover all six projects’ progress.)

I asked Ventura County Homeless Solutions Director Kimberlee Albers if other ERF grant recipients altered their projects after receiving their grant award, as Ojai has. She declined to comment specifically, but stated, “ERF grants are set up to move forward quickly to resolve encampments and unsheltered homelessness. It is important for the funded project in Ojai to progress to preserve these resources for the community.”

(I’ll note that Ojai’s ERF application optimistically predicted the project would be up, running, and fully populated by Jan. 15, 2025.)

The Ojai City Council, meanwhile, has approved its new project location twice now (over the objections of some neighbors), most recently on March 25. The Council, led by new Mayor Andy Gilman, signed off on the former Council’s location choice with a 3-2 vote.

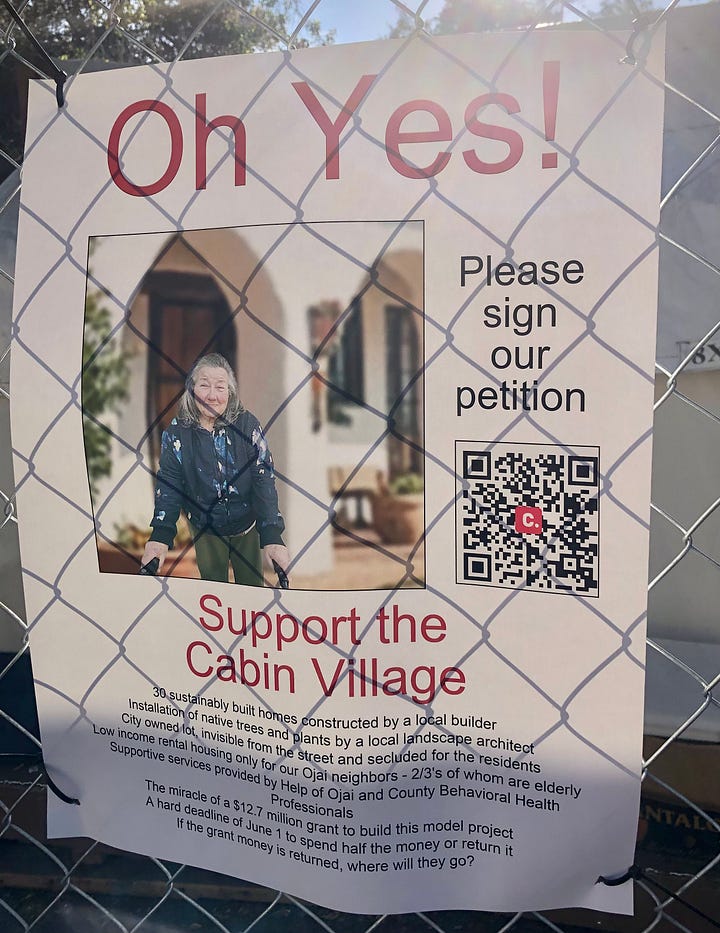

Ojai Tent Town residents and supporters, sensing the importance of the March 25th vote, displayed posters urging a “yes” on the project. The posters hung on the exterior of the chain-link fence separating the tents from the general public.

The area neighbors’ representative on the Council, Kim Mang, voted against the housing site location, as did Councilman Andy Whitman. Both raised budget concerns.

Mayor Gilman, alongside Councilwomen Rachel Lang and Leslie Rule, comprise the majority in favor of the site. (I’ll note that even though we have a reorganized Council, we still see a familiar 3-2 vote split — interesting.)

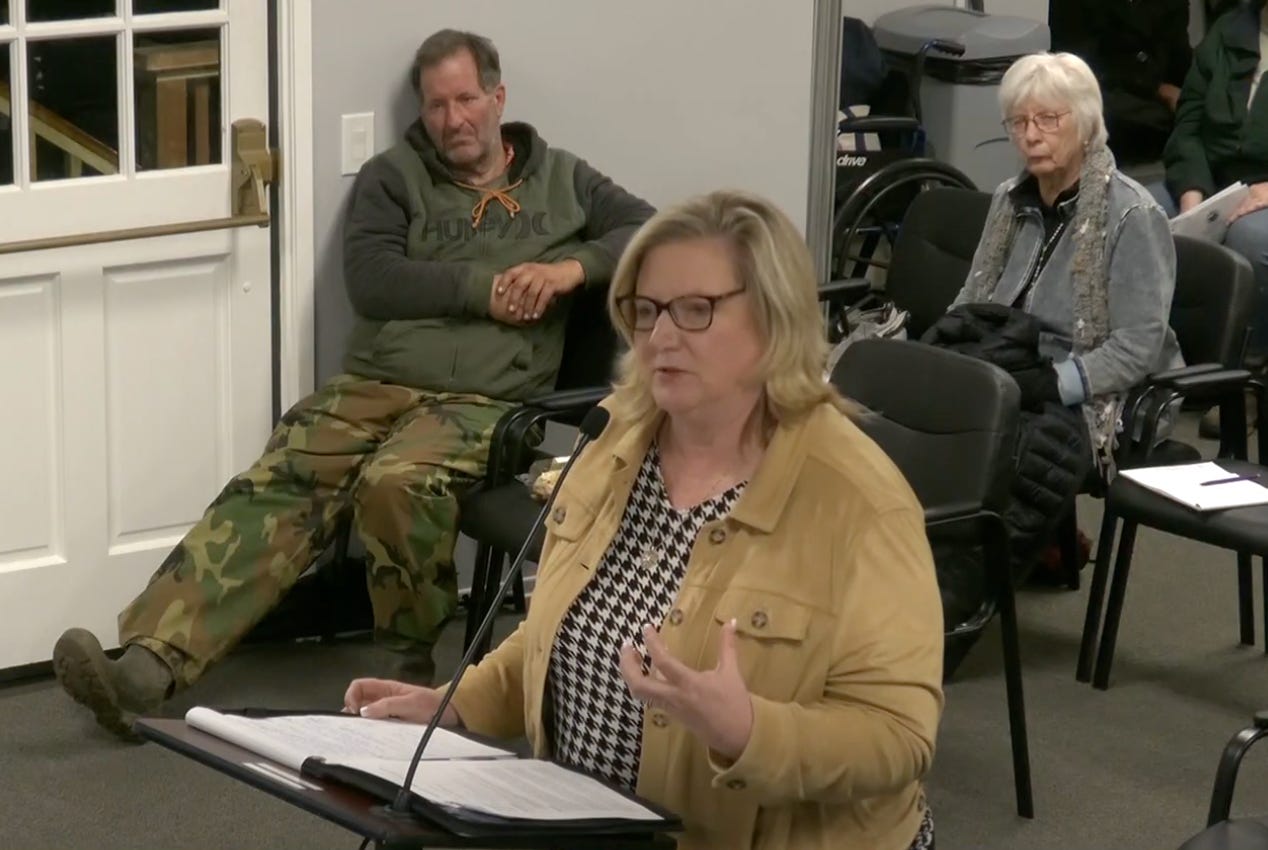

As with each of the proposed locations for the Cabin Village housing development, some nearby neighbors, particularly Persimmon Hill residents, spoke in opposition to the plan March 25th. They were outnumbered by supporters of the overall project and its location.

To be clear, there are neighbors of the public works yard who enthusiastically support the project. They call themselves “Friends of the Cabin Village.” One member of the campaign reminded me, “I live closer to the public works yard than the majority of houses in Persimmon Hill.”

And although the Council has spoken twice on the topic, we cannot necessarily say the political fight is over.

I will remind readers that we’re speeding toward a financial deadline: grant recipients are required to expend 50% of their grant allocation by June 30, 2025.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. A new character has entered the story.

Meet Clay Creasey (and the City’s various cost models)

Persimmon Hill resident Clay Creasey is a recently retired AAA finance executive (he’s also the former Chief Financial Officer for Toys “R” Us). Creasey told me he began researching the proposed Cabin Village project in January 2025, at the request of his Persimmon Hill neighbors.

Given his background in finance, Creasey began his research with a review of the City’s “cost model” for the housing project’s first year of operation.

City staff initially scheduled the cost model discussion for January 28th. Then they delayed it until February 4th. In the interim, Creasey found a “rookie math error” in the City’s model. “That kind of lit my fire,” he said. A revised version of the cost model was included in the City’s 800-page March 25th staff report (The full report is too large to link, though you can find it here under item two. An image is below.)

Creasey made another discovery while reviewing the City’s monthly Treasurer’s reports.1

“The city actually got the [ERF] money last October. And when they received it, they put roughly 6 million, half of the grant, into a treasury bill investment, which is an okay place to put money,” he said. “The other half got put into a bank account that earns no interest at all.”

Before we dive too far into the specifics, though, I want to first acknowledge the thesis inherent in the City’s cost models: that Ojai can sustain the ERF project financially through its first year of operation without digging into its own General Fund.2

How would that work, exactly? Let’s take a closer look at the City’s revenue model.

The City identifies two primary revenue streams for the Cabin Village’s first year of operation: interest income from the $12.7 million in state funds, and rental income from the residents. Let’s talk about interest income first — it’s the largest revenue source in the cost model.3

Here’s how the City describes its projected interest income: “the City of Ojai will enjoy the benefit of interest income accruing on the $12.67 million grant award. The interest allocation will be reduced over time as the City draws down the grant award in accordance with the guidelines of the ERF Grant.”

That makes sense in theory, right? Assistant City Manager Carl Alameda told me in early April that “the City of Ojai has placed the ERF Grant award in the City’s account with the State of California Local Agency Investment Fund (LAIF).” He explained, “LAIF is a pooling vehicle that local governments/agencies can place excess funds in… and earn a higher rate of interest than a money market or similar basic banking account would offer in a safe manner with the benefit of daily liquidity.”

But remember what Creasey said about the City placing half of its grant funds in an account that bears no interest?

A review of the City Treasurer’s monthly reports (the most recent one reviews March 2025) shows that indeed, the City initially split the grant award between its cash account and treasuries. The City moved $3 million into LAIF in early January, another $3 million into their LAIF account in February, and $9 million into LAIF in March. (Obviously, there are more than just ERF dollars in this account. Prior to receiving the ERF grant award in October, the City’s LAIF balance was 1.7 million. As of March 2025, it’s $16.7 million)

Creasey acknowledged the move via public comment during the April 22nd City Council meeting.

“Christy, thank you for investing nine million dollars in the LAIF fund on March 24th,” he said. “Because of that, this City will make roughly $100,000 more in interest in the balance of this year than it would have had it continued down the path it was going prior to that.”

Wait — who’s Christy? Interim Finance Director Christy Billings replaced Pam Greer (who had been in the Finance Director role since 2019) in March 2025, according to the Ojai Valley News.4

And why did the City wait until 2025 to invest money it received in October 2024? Neither City Manager Ben Harvey nor Assistant Manager Alameda responded to that question. In Creasey’s experience, “failing to invest $6M costs about $20,000 per month.”

Moving along — let’s talk about the City’s other primary projected source of revenue for Cabin Village operations: rent. Each of the 30 units will qualify as affordable housing, which means the rent is restricted to approximately 30% of the tenant’s income. And yes, some potential Cabin Village tenants do earn income. Some receive earned benefits like Supplemental Security Income (SSI) from the federal Social Security program. Others have local jobs; some have no income whatsoever. All of this in mind, the City projects that it will receive $59,500 in annual rent payments. I asked Alameda to explain how he got there:

“The majority of the residents at OTT receive SSI benefits. It is customary that SSI recipients pay one-third (33.33%) of their income when living in public permanent supportive housing,” Alameda explained. “The County of Ventura Area Median Income (AMI) 30% threshold for a single person considered ‘Extremely Low Income,’ at the time of the [March 25th] Staff Report was an AMI of $29,550.”

Let’s break this down. Alameda is referring to county-wide “income limits” for affordable housing. Take a look:

This means that to qualify for affordable housing at the “extremely low income” level, an individual can earn no more than $29,550. That’s why these numbers are referred to as “income limits.”

Alameda said he made a “conservative estimate” that six individuals would pay rent at the extremely low income limit. “Thirty percent (33.33%) of this amount is about $9,850, when applied to six (6) units that returns an annual rent of $59,100,” he explained.

Here’s the thing, though: the maximum monthly SSI payment for an individual is $967. The state of California offers an additional $240 state supplementary payment to extremely low-income adults. Together, it’s a maximum monthly benefit of approximately $1,200 for an annual income of $14,400. (I’m no budget whiz, but it seems like the City may have used the wrong number here.)

Moving along. (We’ll get through this together.)

The other important source of rental revenue in the City’s cost model is what is commonly known as “Section 8,” or the Housing Choice Voucher program. Funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the voucher program is administered locally by the Area Housing Authority of Ventura County (AHAVC).

In a voucher scenario, tenants pay between 30% and 40% of their monthly income toward rent and utilities, and the AHAVC pays the difference using federal dollars. According to Alameda, the majority of OTT residents would qualify for the Section 8 program, “but unfortunately, many of our OTT residents don’t have the knowledge of the program or the ability to go through the process, this is where effective on the ground case management will be key,” he said.5

The City forecasts that it will receive $142,560 in annual rental revenue via the AHACV program. Let’s (quickly) go through that math. In the 93023 area code, the maximum monthly assistance for a one-bedroom rental is $2,200. Applying that number to one Cabin Village unit for twelve months yields $26,400. Assuming six units receive AHAVC funding for twelve months, including a 10% vacancy factor, gets you to $142,560.

There’s a potential wrinkle here, too. The Trump Administration is considering deep cuts to federal social safety net programs like the Housing Choice Voucher Program. They’re also exploring selling HUD’s Washington, D.C. headquarters. (I’m entirely serious.)

There’s one final revenue source we should address, one that currently exists as a “TBD” in the City’s cost model: the County of Ventura. (This is an issue Whitman and Mang often point to.) What’s the deal? In short: funding streams exist, but the money isn’t actually available yet.